mixing memory and desire

lost love, lost faith, lost cities

I.

Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities:

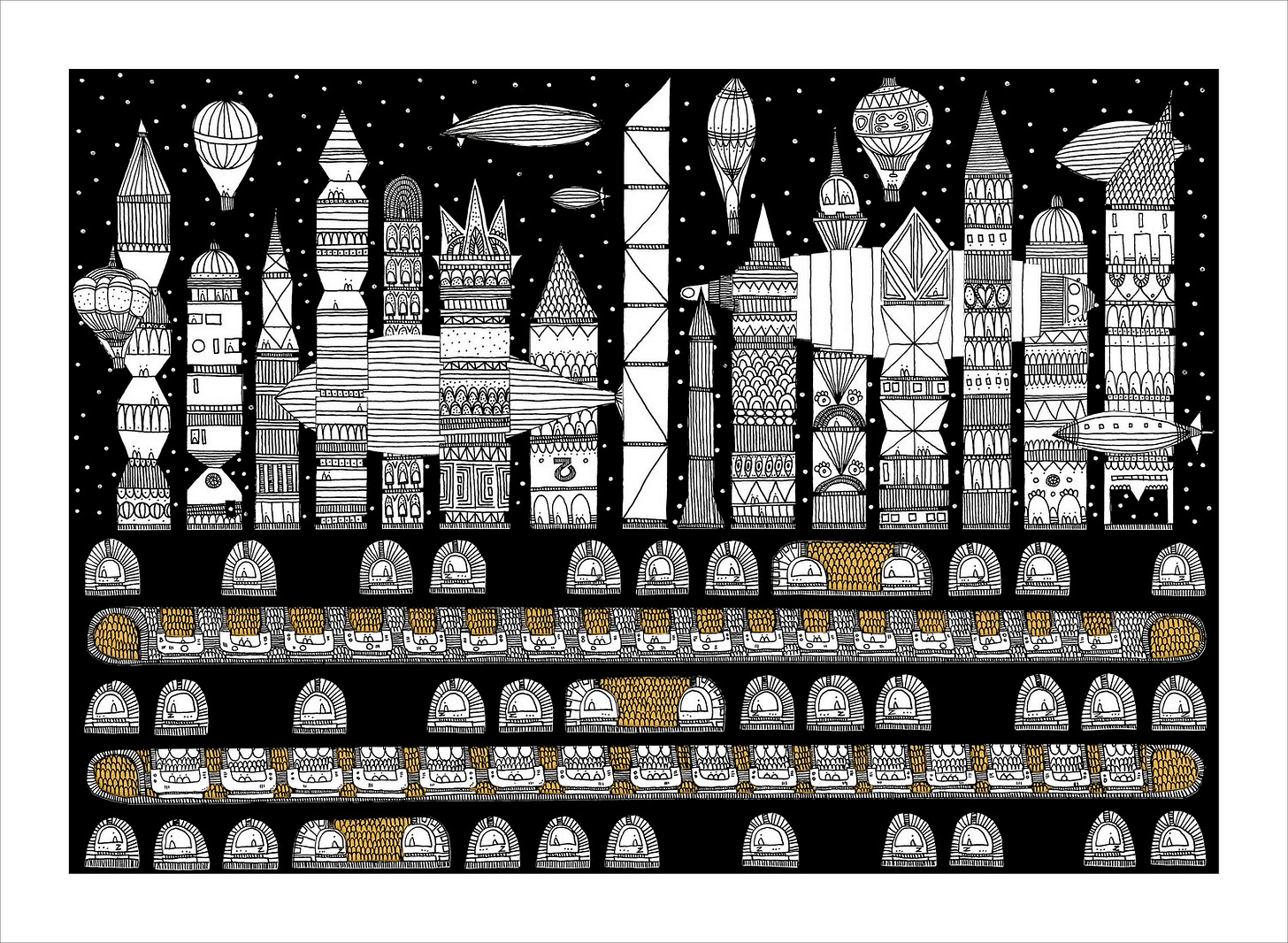

Travelers return from the city of Zirma with distinct memories: a blind black man shouting in the crowd, a lunatic teetering on a skyscraper’s cornice, a girl walking with a puma on a leash. Actually many of the blind men who tap their canes on Zirma’s cobblestones are black; in every skyscraper there is someone going mad; all lunatics spend hours on cornices; there is no puma that some girl does not raise, as a whim. The city is redundant: it repeats itself so that something will stick in the mind.

I too am returning from Zirma: my memory includes dirigibles flying in all directions, at window level; streets of shops where tattoos are drawn on sailors’ skin; underground trains crammed with obese women suffering from the humidity. My traveling companions, on the other hand, swear they saw only one dirigible hovering among the city’s spires, only one tattoo artist arranging needles and inks and pierced patterns on his bench, only one fat woman fanning herself on a train’s platform. Memory is redundant: it repeats signs so that the city can begin to exist.

II.

I dated a machine learning researcher for five years. Once, in her poorly lit bedroom, sitting on the bed that always made my back hurt when I woke up, she drew a bowtie shape on a pad of legal paper and began explaining autoencoders to me.

An autoencoder is a (slightly archaic, though pedagogically useful) means of building a condensed representation of large data. You can train autoencoders to take huge, complex input, reduce it down into a tiny latent space representation, and then reconstruct it back into something mimicking the original. For example, you might take a dataset of handwritten numbers, each of which is an image with thousands of pixels, and train an autoencoder to spit out images as identical as possible to the originals, with the constraint that there must be a bottleneck layer (the knot of the bowtie) that consists of only thirty-two numbers. The idea being that those thirty-two numbers reveal some essential structure of the data, like stroke thickness or curvature, that isn’t immediately obvious from a noisy collection of pixels.

In Zirma’s case, the essential structure of the city for the narrator contains the dirigible, the tattoo artist, the fat woman. Key elements plucked from the noise, of every brick laid on every street latticed across land and river and valley. Like any useful representation, his memory of Zirma balances invariance with informativeness: he coalesces every girl with a puma into one, and doesn’t disregard the sailor tattoo shops, though there may only be one. Redundancy is systematically eliminated, then generated.

I question my memory. I think back and wonder: am I certain it was her bedroom? Perhaps it was mine, the attic room with the slanted ceiling, mattress on the floor, LED strip lights blushing purple. Was it the legal paper, or one of her spiral notebooks—was this before or after I bought that ten pack of legal pads from Amazon? Did my back really always hurt when I woke up, or do I just remember the bed being too soft when I first laid in it? Infinite details populated from some condensed representation built by a idiosyncratically trained autoencoder, practiced at constructing romantic self-mythologies from real-world events.

In preparation for this essay, I asked the chatbot she now develops for an explanation of autoencoders, which is eerily like asking her to explain them to me again, though now through the veil of prompt and matrix. Once upon a time we might have been mistaken for identical images, twin input-output pairs of a well trained autoencoder. These days, when I chat with the language model, or even text her with friendly affection, I am keenly aware of how misattuned our bottleneck layer is, compared to how it was. Glimpses through the tiny keyhole of a door now locked.

III.

Christmas in New York City, after I neglected to buy plane tickets home until prices skyrocketed. I sit in a tiny chapel for no reason other than pure sentiment; I’m far past the age where my parents, thousands of miles away, have the authority to usher me into the car to sit, distractedly, through a sermon on the birth of our savior.

We actually never even went to church on Christmas day—the holiday itself was reserved for gift-giving and a long afternoon meal with my father’s parents. The church I attend also bears little resemblance to the church of my youth: the adornments are different, elaborate embroidered gowns compared to the severe suit jackets worn by the men at the pulpits of my childhood; the congregation is small and old and mostly white, so unlike the huge intergenerational Chinese church I grew up in.

In my longing I try to rhyme where I am now with where I was as a child: didn’t my austere, Protestant church, built practically like a recreation center, have that lone circular stained glass window, like the stained glass that drapes over the stage I face now? Didn’t we sing some of these same hymns, at some point in time? Don’t I remember these chairs, with the slatted compartments under the seats upon which to gracelessly prop my scuffed sneakers? I am willfully misremembering my past as I scramble to justify why I’ve come—rudely retracing the paths of my youth, in shoes much larger and dirtier, wholly eclipsing those infantile footprints. I am looking for something long gone, and in the process decimating evidence towards its true location.

I am always mixing memory and desire; I might go so far as to say memory is desire, lived experience feeble before the propulsive multiplication of my want, the repetition of select signs so that the city—excuse me—my life, my self—can begin to exist. Lately in my grief I have been living in the theater of my imagination, a world of infinitely replicated dirigibles. I tend to forget the dozens of girls raising pumas littering the streets. Zirma fades irretrievably in the distance and leaves only its echoes, which I then shout over.

Autoencoders are rarely used in practice anymore; they’re mostly an educational tool for introducing the concept of representation learning. But one domain where they’re still useful is anomaly detection: because they’re so attuned to a specific kind of data (say, the handwritten digits), when they receive a new class of input (say, photos of nature), their reconstructions tend to go haywire; they struggle to remake the original data from the low-dimensional representation. Something about this phenomenon puts me at ease, as someone who’s been attuned to a specific kind of data (say, the warm ease of a committed romantic partnership), slowly trying to integrate new input (say, the wild, yet lovely, flux of distributed friendship). Grief may just be swallowing anomaly after anomaly, after anomaly.

IV.

Just before I left New York in July, uncertain of when or if I’d ever return, I began an essay prematurely mourning my departure:

I reduce you, I dehumanize you as I conjure you in my memory, even now. I want you to be like me. But the joy of you is that you are not like me: I turn to you to negotiate our bounds, to delimit myself, to honestly render myself through discourse.

Because—listen!—seeing the sun set over the Manhattan skyline with you—nothing like I ever could have predicted: better. Watching the entire devastating season two of Interview with the Vampire with you—better. Sharing sliced summer fruits over idle, winking conversation—better! Every moment of these two months entirely unpredictable and so much more delightful than my imagination’s feeble capacity; how shameful, then, is it, that I now conjure an echo of your living, breathing body in my mind, glutting myself on an image already loosed from flesh, and spirit, too: for what can you do in my imagination that is not a pastiche of the self you’ve generously exposed to me, over these two months, these two, fleeting months? Desperate and hopelessly happy. Oh, how I miss you. I’m sorry for how I adulterate your full humanity; I’m too sentimental to be an iconoclast.

Maybe I’d have been better off as a Catholic: I love buffing my idols.

V.

What matters? The record-skip of memory: every Friday evening the party where I met you. Desire lines reticulated over the hostile landscape of living. You can populate a city full of people who love you, as well as people who all despise you. Memory merely a trick of the light, the ability to dress the world in the helplessly romantic crush of golden hour, or the ghostly trappings of a winter night.

It all hurts: lost love, lost faith, lost cities. The only salve I know for the hurt is presence. Small things, like remembering to breathe as I walk the ten minutes from the subway to my work. The smell of pickles. White December light. The traffic patterns, the trajectories of moving vehicles. Glittering Christmas lights. The beeps of forklifts, the purr of car engines rolling to stop signs. Murals, street signs, exposed brick. Men smiling in their hard hats. The click of the front door, unlocking.

All I can do is make truer memories for myself in the future. Nothing is redundant under the discerning light of honest attention: everything is only itself.